What makes a man? Is it his ability to withstand pain? The ability to provide for a family? The ability to put others before ones' self? The ability to stare death in the face and not have the courtesy to blink?

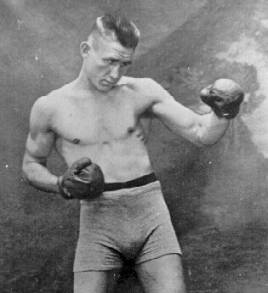

Now imagine doing all of those things. That man was named Billy Miske. He was a boxer from 1913 to 1923. Below is a story written by Dorothy Kilgallen and Richard Kollmar for the January 1951 issue of Reader's Digest.

(Link here)

It's possible you've heard their story before. A handful of famous sports writers have discussed the topic near Christmas time, for this is how the heroic yet tragic legend of Billy Miske came to be...

On an afternoon in 1923, as the first snow of the winter fell on the city of St. Paul, Billy Miske got to thinking about Christmas. As you may remember, Miske was one of the best heavyweight prize fighters of his day. In his ring career of more that 100 bouts he fought Jack Dempsey. Tommy Gibbons and Harry Greb. Only one opponent -Dempsey - ever scored a knockout against him.

He was 29 years old, blond and blue-eyed, muscular and graceful. He looked like a champion. But he was dying, and he knew it.

It was a well-kept secret. The only persons who knew of his condition were Jack Reddy, his manager; George Barton, a sports writer on the Minneapolis Tribune; and Dr. Andrew Sivertsen, who five years before had said, "I won't lie to you, Billy - you have Bright's disease. If you quit fighting and take care of yourself you may live five years."

Billy did not quit. To his wife, Marie, he reported casually that he had "a little kidney trouble," which would be all right with diet and doctoring. Such was his courage and unfailing gaiety that she never suspected that his ailment was more serious than he had admitted.

He climbed into the ring 70 times after the death sentence was pronounced. He made money, and because he knew his fighting days were numbered he put all his savings into an automobile sales business in partnership with a friend. The business was to be security for Marie and the children when he was gone. But within two years the venture was on the verge of bankruptcy. The day after his third fight with Jack Dempsey he used his entire purse - $18,000 to pay debts owed by the partnership.

From then on there were fewer fights and he was paid less money for them. It was a painful struggle for him to train enough to keep appearances for the sports writers.

In January, 1923 Billy knocked out Harry Foley in one round, but when it was over he felt terrible. The doctor had no trouble persuading him to stay home and rest; for weeks he didn't have enough strength to walk around the block. All through the spring, summer and autumn he hung around the house, resting, keeping to his milk diet, playing with the children, while Marie did the housework and worried about the bills.

Now, as he walked the streets on the day of the first snowfall, looking at the store windows, Billy worried, too. The snow made him think how close it was to Christmas, and how bleak the day would be for Marie and the children unless he made some money quickly. He could not bear that Christmas should be anything but the way it had always been in the past - warm and safe and bright and abundant, something to remember.

He knew of only one way to get money fast. It was simple. Hard, but simple. He walked rapidly to Jack Reddy's office.

"Jack," he said, "get me a fight."

The manager looked at him unbelievingly. "You're a sick man, Billy," he said. "Remember, I know all about you. I won't put you in the ring. I wouldn't have it on my conscience.

Billy leaned forward in agonized earnestness. "Please, Jack, I'm flat broke. You know I lost everything in the automobile business. You know about the doctor bills. We've even sold most of our furniture. You've got to get me one more fight so I can give my family a happy Christmas.~ Reddy argued, pleaded, reasoned. He offered to lend or give the fighter money if he would stay out of the ring. But Billy repeated stubbornly, "No, Jack; get me a fight before Christmas."

In the end the manager gave in. A few days later he arranged a match with Bill Brennas, to be held at Omaha. Brennan was a tough fighter. He had battled Dempsey in New York and was ahead on points up to the - 12th round, when Dempsey knocked him out.

Word of the coming Miske-Brennan bout soon reached George Barton. Knowing of Miske's condition, he angrily reached for the telephone and called Jack Reddy.

"Are you so hungry for a buck that you'd risk Billy Miske's life for it?" he said. "You know he isn't in any shape to fight. I'm going to write a story blasting you as you deserve to be blasted."

"There's an angle you don't know about, George~ Reddy answered. "Hold it until I get Billy and bring him over to your office so he can explain."

ln a half hour they were there, and Billy was telling Barton about the debts, the children and Christmas. When he had finished, Billy leaned forward with his big hands clasped between his knees. "George," he said, "you've always been my friend. Do one more thing for me. Don't write anything about me being sick."

Barton said, "Billy, do you realize if you fight you may die in the ring?"

Billy nodded. "I'm a fighter, George. I might as well die in the ring as sitting in a rocking chair waiting for it."

That ended the talk. Barton agreed to keep the secret.

Billy was far too ill to train for the fight. When newspapermen and boxing fans asked why he wasn't working out as usual at the Rose Room gymnasium in St. Paul, Reddy explained that Miske had a gym rigged up at his summer place on Lake Johanna and would do all his training there before leaving for Omaha to work out in public.

Actually Billy was spending most of his time in bed, saving his strength. He left for Omaha only a few days before the fight. Oddly, he was still a fine looking specimen; the illness that was destroying him had not caused him to lose weight or become haggard. Possibly the examination of fighters was merely cursory in those days, or it may be that only a test for kidney ailments (which was not given) would have revealed Miske's condition. At any rate, he had no trouble passing whatever examination there was.

The fight had a fiction-story quality. In the opening round of the match sports writers at the ringside noticed that Brennan appeared much slower than he had been when he made such a good showing against Dempsey, while Miske was fast and smooth. For 121 minutes Billy was not a dying man, even to himself; he was Billy Miske, "the St. Paul Thunderbolt." It was all there - the aggressiveness, the nimble footwork, the "nitroglycerine" punches.

For the first two rounds the fighting was at close range, with Brennan doing considerable backing away. In the third round Billy hooked Brennan with a left and Brennan went down, helpless. The bell saved him as the referee reached the count of five. Brennan's seconds dragged him back to his corner and worked over him, but when he came out for the next round he was obviously still dazed by Miske's powerful punch in the third. Just as he got to the center of the ring Miske met him with a terrific right to the jaw, and lie crumpled to the canvas. He tried valiantly to get up, but couldn't, and was counted out.

As Billy Miske's arm was raised in the victor's salute he smiled, for the last time, at the crowd.

He received $2400 for the fight. He took the purse back to St. Paul and began to do the things he most wanted to do before the end came. He bought furniture to fill the rooms that had been empty since he and Marie sold everything except the beds, a kitchen table and a few chairs. He went on his last duck-hunting trip. Then, as the shop windows began to glow with Christmas red and green tinsel, he went downtown again.

He bought a piano for Marie; she had a lovely contralto voice and had always wanted a piano of her own. He had a fine time choosing gifts for the children - a bicycle and a red coaster for each of the boys, dolls and a teddy bear for little Donna. There was enough money left for a Christmas check for his parents, paid for a Christmas feast, and something Marie could put aside for the need that would come. His shopping finished, Billy went home exhausted and went to bed.

The intense suffering had begun, but he was able to conceal it by staying in his room during the worst hours. He managed to smile and make cheerful conversation every time Marie or the children came near. Marie still had no inkling that his illness was more than a bothersome passing ailment.

She trimmed the tree alone that Christmas Eve. After midnight, when she finished, Billy came downstairs in his pajamas and bathrobe to admire it. Standing by his wife's side, he took her hand and looked for a long time.

"It's the prettiest tree we've ever had," he said.

Marie's heart swelled as she looked up at him. "Billy, you're so good to us."

He grinned. "Merry Christmas, honey," he said, bending over to kiss her. "It is going to be a Merry Christmas, isn't it!"

He was in his place at the head of the table at Christmas dinner, looking the picture of happy, carefree young father with his family around him. In the gaiety and excitement of the children's delight over the tree and the toys, only Marie noticed that Billy ate very little. When he caught her watching him he winked as if he were enjoying it like a hungry kid.

"Gee, honey," he said, "you're a swell cook!"

The day after Christmas he was in agony. Waiting until Marie was rattling dishes in the kitchen, he got out of bed, stumbled to the telephone and called Jack Reddy. "For God's sake, Jack, come and get me," he whispered. "I can't stand the pain any longer."

Reddy came with his car. Marie, terrified, j helped her husband into the back seat, and Reddy drove to the hospital. As Marie sat in the car, holding Billy in her arms, feeling him tremble with the pain, he told her the truth at last.

Six days later, on the morning of the New Year, Billy Miske died.

To Billy Miske. A first-class fighter, an amazing father and man.

No comments:

Post a Comment